How the renaming of Mount Blue Sky honors a deeper story of the land

Mount Blue Sky in Colorado.

A mountain’s history

The story of Mount Blue Sky is a story of people who persevere. It cannot be told without the stories of the Indigenous inhabitants who have known and cared for the land for thousands of years. This mountain, formerly known as Mount Evans, sits at the center of what is now Colorado and is home to the Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway, the highest paved road in all of North America. It’s also connected to the Sand Creek Massacre, where a US volunteer cavalry under the command of Colonel John Chivington violently killed 150–230 unarmed Cheyenne and Arapaho people (mostly women, children, and elders) on the banks of Sand Creek in 1864. That the mountain was named after John Evans, governor and superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Colorado Territory at the time, was yet another painful reminder of the brutal tragedy. Evans denied culpability, but a congressional investigation in 1865 condemned the Sand Creek Massacre and called for his removal from office, which was enforced by then-President Andrew Johnson.

Six Indigenous Nations are known to be affiliated with the area, including the Ute Mountain Ute (CO), Southern Ute (CO), Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation (UT), Cheyenne and Arapaho (OK), Northern Arapaho (MT), and Northern Cheyenne (MT), and at least 48 Native Nations have historical affiliation with Colorado. The renaming of Mount Blue Sky, which was made official by the US Board on Geographic Names on September 15, 2023, can be viewed as just one step in a larger, ongoing progression toward a more honest, equitable, and just public recognition of American, and Native American, history.

The tragedy at Sand Creek was part of a broader period of rapid westward American expansion that forever altered the societal trajectory of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, along with hundreds of other Indigenous Nations across the continent. Today, the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute are the only two Nations physically located in Colorado. And while the renaming of Mount Blue Sky alone doesn’t rectify the past, it brings new opportunities to educate the public on the historical realities of the Sand Creek Massacre as well as the continued presence of Indigenous Peoples across these lands. With one way up and one way down, the mountain and scenic byway provide a prime venue for sharing this important and ongoing story in an intentional and impactful way.

The mountain’s name change in 2023 was the culmination of years of advocacy, particularly by the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma (forced there by the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867) and included wide support from tribal leaders and community members. Front Range residents and entities like the Wilderness Society, the Clear Creek County Board of Commissioners, the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board, the Southern Ute Tribe, and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe helped advance the name change in honor of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations. The name “Blue Sky” carries much significance, as the Arapaho are known as the Blue Sky People and the Cheyenne hold an annual renewal of life ceremony known as Blue Sky.

An honest recognition and opportunity for awareness

With a new name and a scenic byway already under construction, the US Forest Service used the opportunity to develop new interpretive signage that honors the history and cultures of Indigenous Peoples on Mount Blue Sky. They contracted the National Forest Foundation, who was familiar with the cultural resource study and tribal consultation Sweet Grass conducted for America the Beautiful Park in Colorado Springs, and asked us to engage with tribal historic preservation officers from six Indigenous Nations for tribal input. This led to a 10-month participatory process of outreach, interactive discussions, workshops, and interviews with Indigenous knowledge holders that culminated in suggested sign content, verbiage, and location recommendations based on the findings.

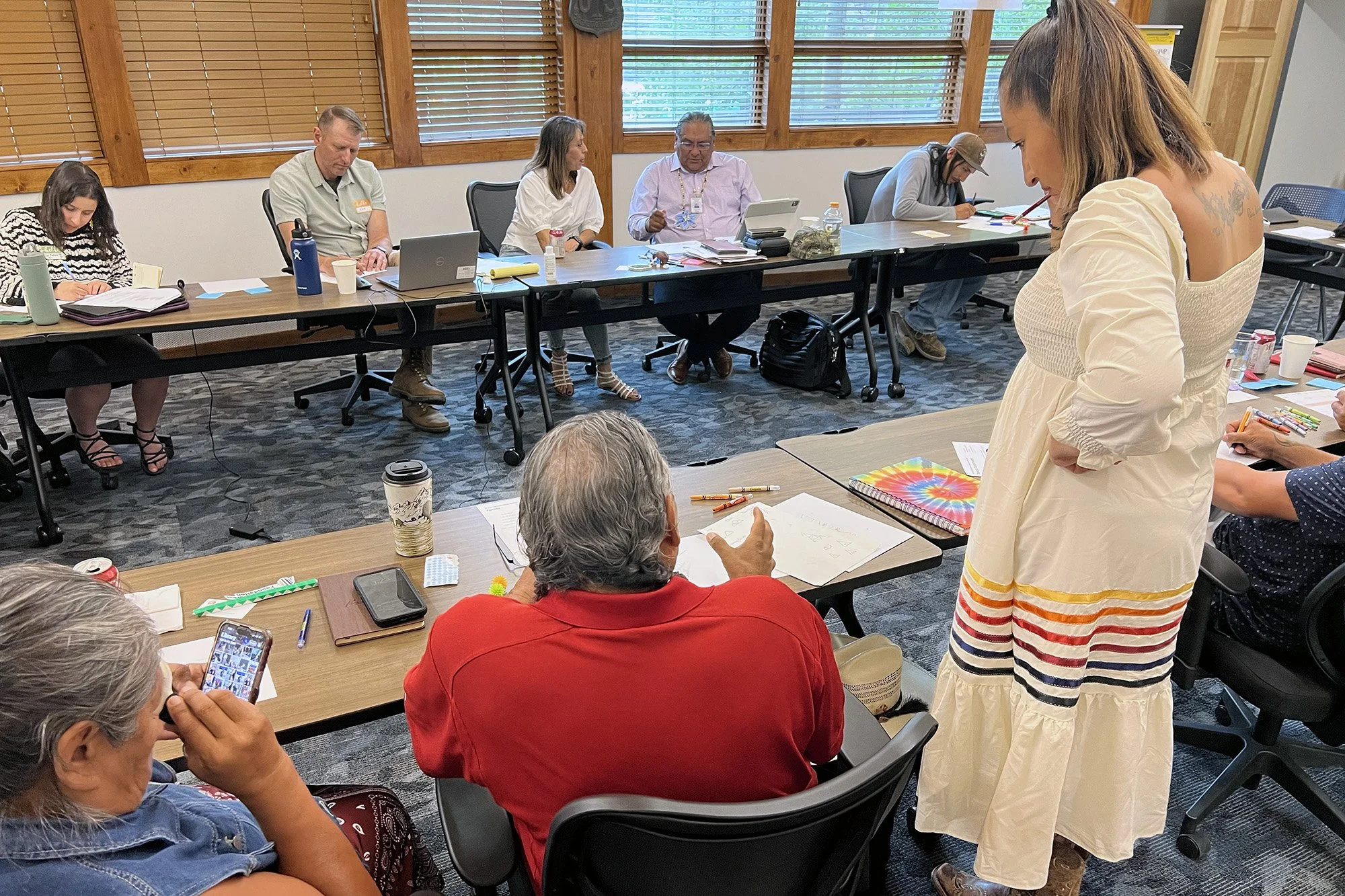

Workshop participants create their own sign ideas at the Clear Creek Ranger District Office in Idaho Springs in July 2025.

The intended audience for the updated signage is everyone who visits the Mount Blue Sky Scenic Byway. Though the audience is massive and diverse, it can broadly be split into two categories: those who are Indigenous, and those who are not. For Indigenous visitors, project participants want the signage to connect them to their ancestors, and to the land. For non-Indigenous visitors, a sizeable portion of the public has limited understanding of the true history of Indigenous Peoples in the United States and little education on the specific historical moment that the mountain’s renaming is tied to. For those visitors, the signage can provide a much-improved understanding of the cultural perspectives and historical presence of Indigenous Nations with affiliation to the area. It may even spark a deeper curiosity in knowing the people and stories surrounding the names of landmarks and other geographic entities in their own day-to-day environments.

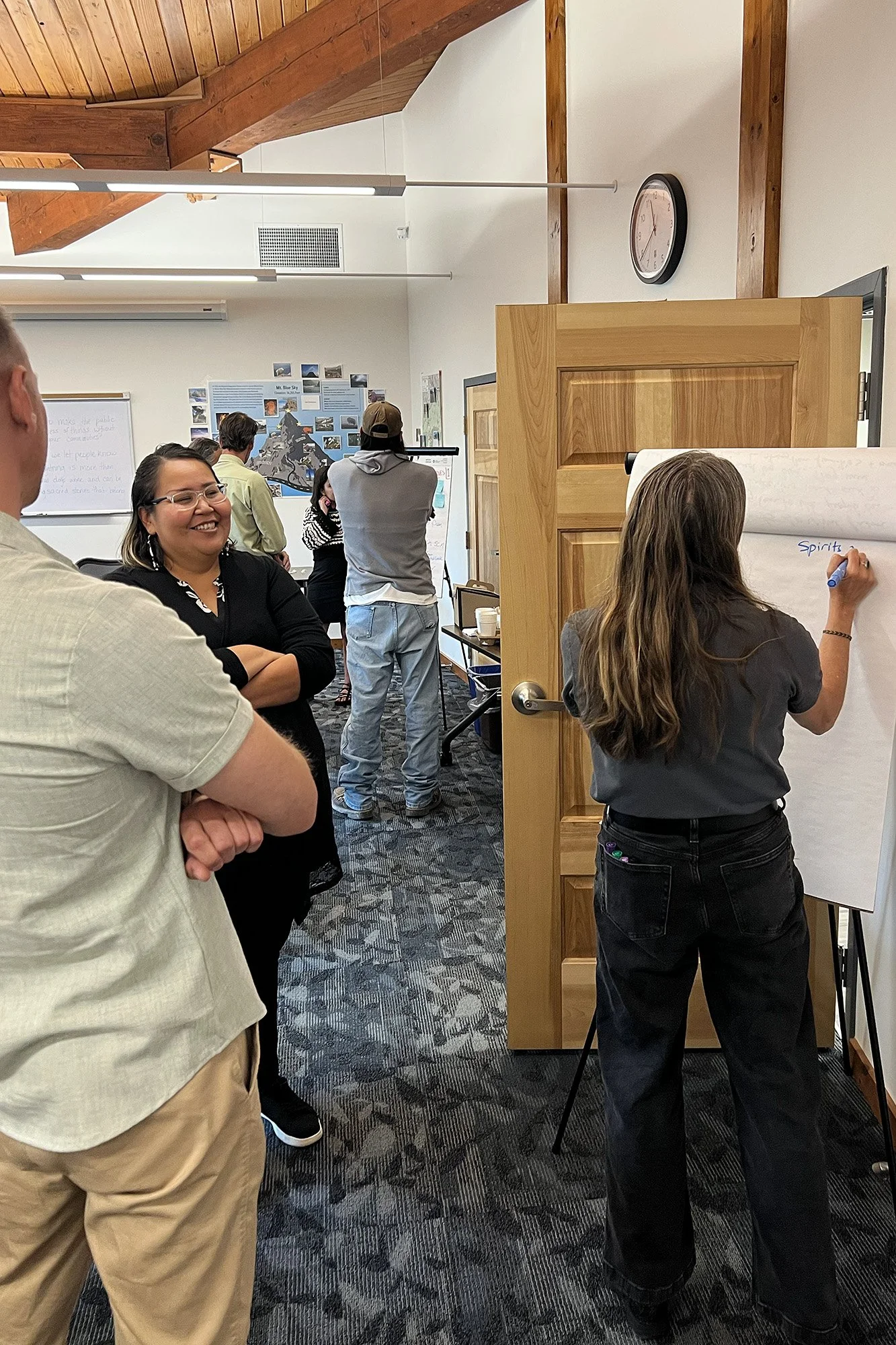

Workshop participants generate ideas for signage themes and content at the Clear Creek Ranger District Office in Idaho Springs in July 2025.

Participants taking in the view during a group trip up the mountain during the July 2025 workshop.

The politics surrounding Mount Blue Sky don’t end with what happened at Sand Creek. In July 2025, a conservative group in the area vehemently disagreed with the name change and lobbied the Trump administration to revert it back to Mount Evans. They claimed Evans didn’t personally order the Sand Creek attack and should be honored for his other contributions. But tribal leaders say Evans facilitated and fermented the political and cultural environment under which the attack happened, and his name carries deep trauma for their people. This project was, and is, one of countless projects ensnared in the political upheaval of the moment, but as of now, efforts to revert the name haven’t gained much traction and the name “Mount Blue Sky” remains. This along with federal budget cuts and ongoing furloughs of park services employees may one day affect the final installation of the new signage on Mount Blue Sky, but that hasn’t deterred those dedicated to the project, nor will it erase the true history of the mountain.

The renaming of Mount Blue Sky and the reimagining of its interpretive signage represent a more honest public memory and deeper recognition of the Indigenous Nations who have always been connected to this land. While no sign can capture the full weight of these histories, the process of consultation and collaboration has brought forward the voices and perspectives of the land’s earliest inhabitants and will surely give visitors a greater understanding and respect for Native land.

Teanna Limpy, tribal historic preservation officer for the Northern Cheyenne Nation, during a group trip up the mountain during the July 2025 workshop.

Share