14 questions with Sweet Grass co-founder, Andrea Mader

Andrea hikes Mancos Canyon on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation in Colorado during a summer internship at Metro State University.

Sweet Grass recently marked its 12th anniversary, and we sat down with co-founder Andrea Mader to reflect on over a decade of growth and service. Community remains central to the work, and the relationships Andrea’s cultivated over the years is proof of that purpose. In this Q&A, Andrea shares stories of Sweet Grass’ beginnings and the mentorship that made it all possible.

In 2014, what was your original vision for the company, and how has that vision evolved over the years?

Back then, we were really just doing the work. We had so much to do that we didn’t talk much about the vision of Sweet Grass. Michael and I are very different people, and while we’d worked together here and there on projects at Colorado State, we hadn’t done this level of integrated focus. We knew enough to protect ourselves and the work, so I suppose the vision at that time was to formalize what we were already doing.

Sweet Grass was founded on the principles that Kathy Pickering, our mentor at CSU, trained us on, which was to do good work in Indian Country. We knew that meant coming from a lens of participatory research and making sure we were grounded in listening, staying in the background, and not putting expectations on the community. We wanted to keep doing that in an informed way. That's kind of the vision right there: to be optimally unprepared. To us that means bringing our backgrounds and assets to the table, but not being extractive with our research. We want to remain adaptive and responsive to what we're seeing in the work.

Data sovereignty is at the core of Sweet Grass’ work. What motivated you to pursue this approach, and how has it shaped the company’s identity?

For me, the idea of data sovereignty harks back to Kathy’s teachings again, and to participatory methods in general. Anthropology, and applied cultural anthropology in particular, tries to mend the wrongdoings of the academic system. Our training with Kathy and all the literature we read in school really solidified the concept of data sovereignty for us and made it the focus of our company.

Our approach to data sovereignty means communities define what they need and come to us to help them make it a reality. Communities lead the effort and the decision-making. They know the questions they want answered and what to research. We don’t come in with a research idea and impose it on them.

Something I’ve learned over the years is that capacity goes hand in hand with data sovereignty, especially in research. We can collect all this data, clean it, anonymize it, and give it back to the community (which we’ve done many times), but folks need the ability to actually engage with it. Acting on the data is essential in data sovereignty, and that’s been harder to accomplish than I thought.

There’s often a barrier to access and training in data technology (even Microsoft Excel has access barriers), so advanced software is even more costly and difficult to train on. Knowing how to analyze data and interpreting it with as little bias as possible is difficult, too. But the most common barrier we see is time. Our clients know data and impact are important, but it’s hard to prioritize them with so many other emergent issues.

What led you to this industry, and were there any personal challenges or barriers you needed to overcome?

In high school, I started learning about international issues, like international development and women’s studies, and decided to get a degree in international studies. I really wanted to go to China (to do what, I don't know), but that's what I wanted to do. Portland State University had a good international studies program, so I enrolled there and started learning Chinese (which is a very hard language to learn!). I took an Intro to Cultural Anthropology class and something clicked. Learning about research, ethnography, and engaging with different communities definitely felt like the right thing for me. I was also very homesick, so I went back to Colorado to start my undergraduate degree in cultural anthropology at CSU.

Working in any community presents its challenges. Sometimes my personality or identity doesn’t “click” with a particular client or individual. When that happens, I rely on my team. I’m grateful when someone else can meet the needs of a client or understand them in a different way. As an introvert, I’ve also had to push myself out of my comfort zone to become more engaged and present, especially at events and conferences.

What role did mentorship play in your journey?

I wouldn’t be where I am today without our mentors. Sweet Grass wouldn’t have become a business without them either. Kathy was very foundational, of course, but there’ve been lots of other people: Lori Pourier from First Peoples Fund, Eileen Briggs from Cheyenne River Tribal Ventures, Ivan Sorbel from the Pineridge Chamber of Commerce, ethnobotanist Richard Sherman, and Kim Tilson-Brave Heart who brought me to a sun dance and a healing ceremony, and shared cultural experiences that will stay with me forever. Then there are folks like Lakota Vogel from Four Bands Community Fund and artist Walt Pourier who feel like our peers, but are mentors and role models at the same time. All their teachings and stories have made us who we are. I really can't understate just how essential mentorship has been for us.

Andrea receives an award from Dr. Jack Schultz, High Plains Society for Applied Anthropology, for her role as managing editor of The Applied Anthropologist.

What are some of the biggest challenges Sweet Grass has faced, and how have you dealt with them?

Most of the challenges have been in running the business itself. We’ve had to learn painful lessons in finding the right business partners to help with things like taxes, payroll, insurance, or legal advice. Building relationships takes a lot of time, especially when you start a business from nothing and don’t have a strong network. Just like any industry, who you know gets you through.

That’s been true for people management, too. We do specialized work with a specific clientele and finding the right fit for new staff members can be challenging sometimes. We’re trying to build the team in the right areas in the right way while building up the business at the same time. As co-owners, Michael and I have had to navigate interpersonal conflicts as well. But part of owning a business together is learning how to get on the same page.

What are the most rewarding aspects of what you do, and what are you most proud of?

When I come to work every day, even if it feels small, I believe I'm making a difference. We’re helping organizations do really impactful work on the ground, and that’s very rewarding. For me, personally, as someone who likes change, solving problems fits my personality. I love learning new things, so shifting and changing scratches that itch.

I think, overarchingly, I’m most proud of the relationships we’ve built with our clients. And when they recommend us or talk about our work to others in the industry, it feels amazing. I recently worked on a strategic planning project where I was thrown into the deep end of a very tenuous board situation. I helped guide them out of it, but it was a challenging moment for me and two board members resigned in the process. That’s what was needed, though, and I received a lot of appreciation for that work.

As a supervisor and director, it’s also rewarding when things click or go really well for staff. Several years ago we did a market study for Akiptan, and it was one of the first projects Michael and I could step away from and let staff members manage entirely on their own. That was a big deal for all of us, and it felt really good to be building our internal capacity and passing the baton. And that just continues to happen as we bring new staff into the fold.

Andrea with fellow undergraduate and graduate researchers Amanda Bills (left), Ashley Lovell (center-right), and Megan Murphy (right) in 2013.

From your perspective, what are some of the key moments that helped transition Sweet Grass from a small research team to a full-service consulting firm?

There was a major turning point when two key employees left a few years ago. It wasn’t on the best terms, and it was on the coattails of one of our lowest-profit years ever. It was the first time we had to hire people we didn’t know, so we really had to think about what kind of team we wanted to build and how to do it. There was a similar point in 2023 when we grew our team really fast to manage the workload. A lot of new staff came on and there were some growing pains. There was also a lot of momentum, and it pushed us in new and different directions. It shifted the way that the company runs and really transitioned us from a tight-knit five-person team to a larger, intentionally built team.

In terms of the work, there’ve been a few projects over the years that have generated a lot of traction. Our work with Cheyenne River Tribal Ventures, Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation, Oweesta, and Four Bands got us pretty far. I think it also has to do with us keeping our heads down and just doing the good work, over and over again. It's less about key moments and more about the relationships we continue to build.

Sweet Grass honors the knowledge and practices of Tribal Nations. What does “honoring” mean to you in the context of the work we do for our clients?

For me it means not having to ask Indian Country 101 questions. We know the history of colonization, treaties and removal, reservations, allotment and assimilation, termination and relocation, and self-determination. We know the trauma that’s been caused by mass genocide, boarding schools, and intentional wealth extraction. We also understand cultural and spiritual approaches, Indigenous methods, and ways of knowing. Most importantly, honoring Tribal Nations means knowing how to come to communities in partnership, and being open to listening, changing, and acknowledging that they're the experts.

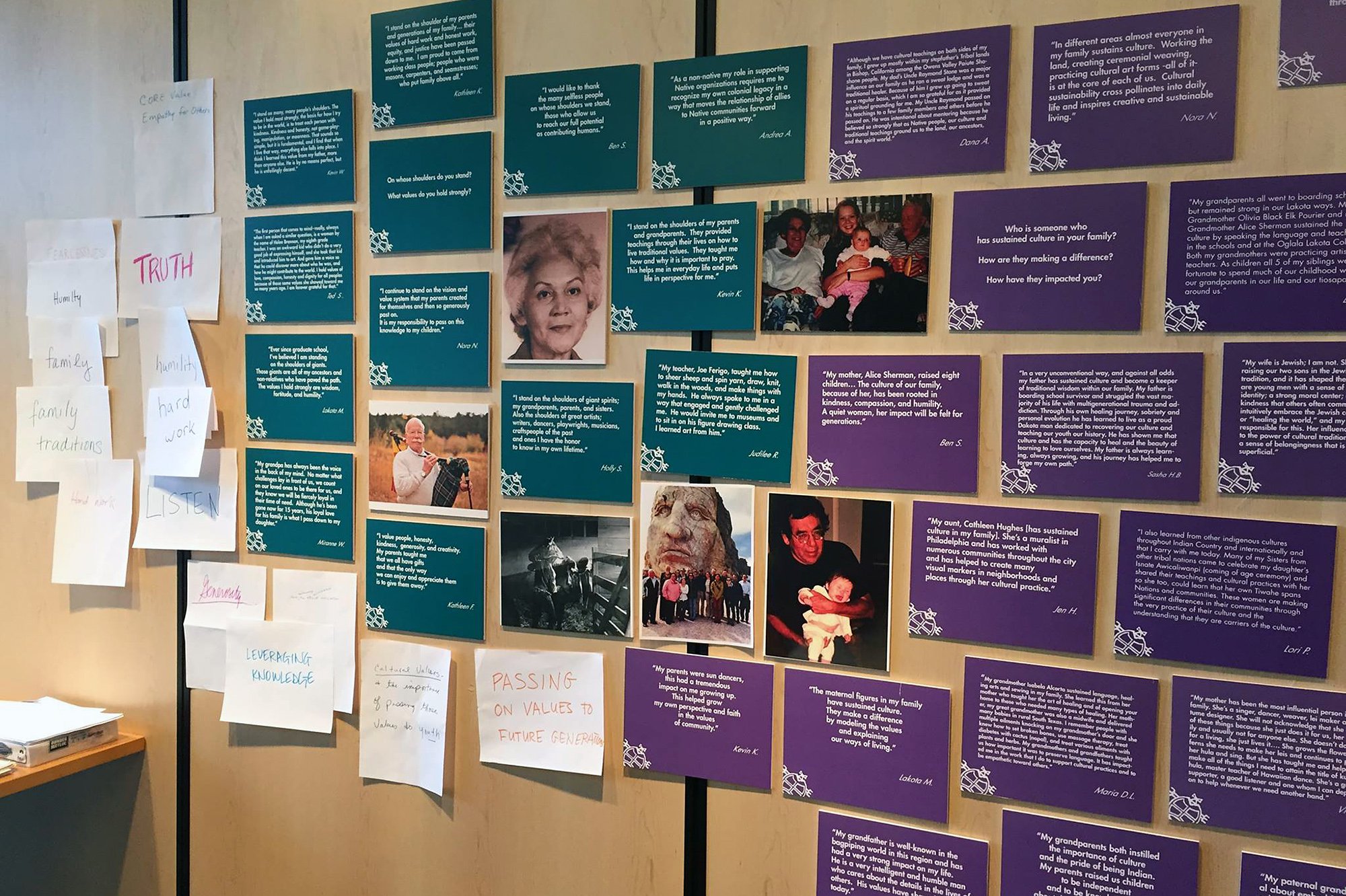

Inspirational culture bearers on display at an event at First Peoples Fund. Andrea shares a photo of her grandfather holding his bagpipes (bottom-left) and one from her wedding day.

Were there any industry or national developments that influenced the business or caused you to shift priorities or approaches?

Most of the federal funding we see focuses on jobs and economic development. We’re responsive to that, so our projects naturally evolve to support those spaces. It’s the same thing with housing and agriculture. There’s been a lot of movement and funding from the USDA, so we’ve done quite a bit of work in Indigenous ag and food sovereignty. That said, there are clear spaces where having white allies isn’t as appropriate. Missing and murdered Indigenous women and relatives, for example, is more sensitive and private, and we want to make sure we’re being allies in appropriate spaces.

Sweet Grass strives to build strong relationships with clients. How have you maintained that community-centric approach, especially as the company has grown and expanded its services?

It's about showing up, and doing what we say we’re going to do. We also share our personal lives and important moments with our clients, and that naturally builds strong connections. It’s about being real and going above and beyond whenever you possibly can.

When we bring on new staff, an essential part of their onboarding is reading and engaging with foundational literature. Some staff come to us with a background in Native communities, and those who don’t tend to have experience working in underserved and disadvantaged populations, so the connections and similarities quickly help them understand the impacts. Michael and I do a lot of travel with the team, so we’re able to mentor and witness how Sweet Grass engages with the community and clients. Team members also travel on their own to explore reservation communities, and they understand how important it is to be resourceful and respectful.

An event at the South Dakota Indian Business Alliance with future partners Kim Tilsen-Brave Heart (left), Nikki Foster (center-left), Sharice Davids (center-right), and Karli Miller (right).

What’s one thing you’ve learned about leadership that you didn’t know when you first started Sweet Grass?

I feel lucky that leadership is kind of baked into who I am, but one of the hardest parts about being a leader is not holding your tongue and doing it in a respectful way. You have to be upfront and share what you truly feel. Passive aggressiveness can eat you alive.

What are other lessons you’ve learned from running the business for the last 12 years?

Find the right partners to do the things you don’t know how to do. Build relationships and always work to improve interpersonal communication. It's not easy work and it may take a long time to pay off, but you need the right people in the right places at the right time.

What role has technology played in the evolution of Sweet Grass?

Technology has always been part of our approach, even when we were only using programs like Microsoft Access and Excel. Like many industries, technology has evolved to support our work. We’ve invested in learning technology that supports research and evaluation like Outcome Tracker and Salesforce, but also online data collection tools like SurveyMonkey, Formstack, FormAssembly, and Fulcrum. We’re also learning data mapping and visualization tools like ArcGIS and Tableau. That said, there are many times when we go back and use good old Microsoft Excel.

Because of our longstanding role as researchers, we’ve become trusted tech advisors for a lot of our clients. We understand and engage with complex technology so we can translate their effectiveness to on-the-ground Native nonprofits. In that effort, we try to stay up to date on the latest tools. We want to know what they can do and how they can help our clients. We’ve certainly adapted to different technologies over the years, but technologies come and go. We never want to lose sight of the humans behind the tools.

Andrea enjoys archery during field school in 2015, an annual event she hosted with Michael. Other activities included hiking, swimming, and rock climbing.

Looking ahead, what excites you most about the future, and what do you want to see?

The type of work we do has grown and evolved so much over the years, I don’t think 12 years ago we could’ve imagined what we’re doing now. If I try to envision what another 12 years looks like for Sweet Grass, it's pretty hard to do! Things are always changing, and we change along with them. In the next few years, though, I’d like to partner more with architecture and engineering firms, and maybe even archaeology. We’d love to do more environmental projects like Mount Blue Sky and Colorado Springs — to honor history while learning what folks want to see happen with natural resources.

It’s always been, and is still about, supporting communities who need it most. Sure, growth is new and exciting, but we want to continue to be the best partner we can. Really, that's the most exciting thing.

Andrea watches the sunset at Sheep Mountain Overlook on the South Unit of Badlands National Park in 2012.

Share